Loren Eiseley’s essay, “The Star Thrower” (1978), describes a man who spends the night on the beach and wakes up to an ebbing tide that has left thousands of starfish stranded on the beach and baking under a hot sun. As he walks along the beach, he wonders, “Is this God’s plan? To what end could this genocide possibly serve?” As far as he can see, millions of starfish are dying. At the same time, others are running around excitedly collecting them as souvenirs. But then, he notices a distant figure standing up, then bending down, and again standing up. As he begins to run toward the figure, he can see that it is, indeed, a man picking up a survivor in a tidal pool, and one by one, throwing these starfish out into the sea. Millions of starfish, destined to perish, yet he is not deterred from saving what few he can. Imagine: saving starfish, even while others seem to rejoice at their demise, and not even God seems to care!

I used to look up to the Heavens and see countless stars in the universe and say, “Nothing really matters, does it? We’re too small to have any real impact. More than likely, the world will get too hot or we’ll blow it apart, regardless. So, what’s the point?”

And so, one morning 30 years ago, I found myself volunteering in a Disabled Children’s Hospital in Nepal, a country a fraction of the size of Washington with tens of millions of people (no one knows exactly), … most of whom are desperately poor and malnourished. I was experienced in surgical assisting and wanted to help, but realized I had a steep learning curve. Here, a turkey baster was used for suctioning, carpenter tools for pinning fractures, but what was sorely lacking were emergency generators, as the power would go off several times a day. In the dark, everyone would reach for the sterilized flashlights, aim them onto the surgical site and the surgical tray, and begin hand-bagging the patient while pushing aside the now useless ventilator.

I imagined the hospital was a time machine that took me back to an earlier time when there were oil lamps, when patients believed evil spirits caused illness, and when antibiotics would be seen as magic elixirs. After 3 months, I was totally spent and flew back. I was so overcome by it all that I still tear up when I think of that first step onto the beachhead. Are these tears for the suffering those children endured, or for the futility of it all? So many starfish, and these were just the few who were barely surviving in a lone tidal pool on the beach!

When I returned 3 years later for more punishment, I discovered that the old converted apartment building of a hospital had morphed into a brand-new, state-of-the-art hospital built by funds raised by a French Organization with Emergency generators, a Prosthesis Lab, and Occupational and Physical Therapy Departments! The 20th century had arrived in Nepal, just before the 21st c. began! To hell with appropriate technology, we could now deliver quality care to lots of children!

So, this time I had the opportunity to look out at the beach and get an appreciation of the bigger problem that lay beyond. In doing so, I met a starfish, or rather a street urchin, Uma, who didn’t know her age (perhaps 8-10 years old). Uma sold cigarettes after school for her mother while diligently doing homework on the front doorsteps of a tourist shop, and we became friends.

Dazzled by her success, “How could this be?” All I did was throw her back into the sea to give her a fighting chance. $200 each year – nothing more! I didn’t feed her, but I fed her hunger to survive and better herself. She had to continue selling cigarettes on the street while doing her homework in her lap! Soon, like all the other kids in her class, she too wanted to become a doctor. This environment isn’t found in the overcrowded, if free, public schools. Moreover, public schools teach only basic English (a requisite for a profession). Today, Uma is happily married, raising a son, and working as a nurse in Dubai – where she earns 25 times more than she had been a few years ago as a nurse in Nepal. Now she can provide for her elderly mother and in-laws, who require medical care.

After the allotted 3 months, I left Nepal, having enrolled Uma in a private school where she could become fluent in English. She was demoted from the 3rd Grade to Grade 1 to learn English, but subsequently she skipped a grade each year until she had caught up to her rightful grade and had become #1 in her class. Being a private school, her class was full of high caste, wealthy students whose parents had money, homes, books and spoke English! Uma had only her school uniform and textbooks (which we provided), and an illiterate mother and half-brothers. Her father abandoned the family.

And so, Uma showed me how a starfish can become a Star Fish. We email regularly, and she calls me “father”; and like my own daughter, she is independent, self-assured, and lovingly-kind. But best of all she is helping others. Uma’s transformation transformed me. I worry not over my petty problems in comparison, but focus on those starfish left to the elements, esp., the few surviving in tidal pools, who when flung out to sea, know how to thrive and take on the predators of the deep.

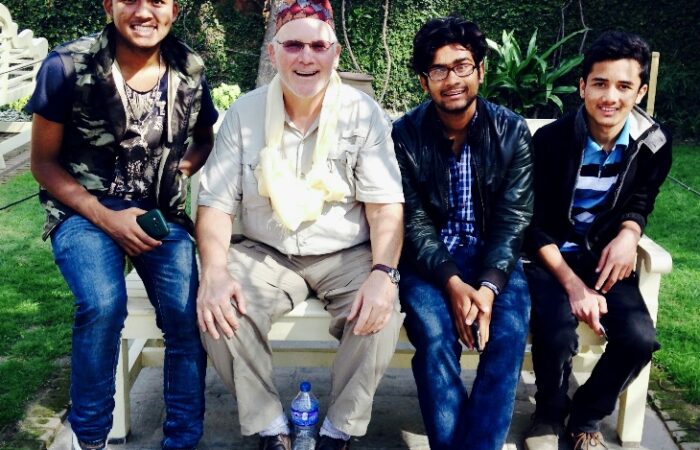

And that was how ANSWER (American-Nepali Students’ and Women’s Educational Relief) was founded. Now, we are in our 25th year and have helped more than 1700 highly disadvantaged children (including 3-4 dozen sponsored by SUUC members) gain a quality education. Now, as doctors, nurses, lawyers, engineers, bankers, accountants, etc., they are undercutting the caste system. Amazingly, Uma’s metamorphosis spawned my own growth from despair to hope and ultimately, to gratitude—all for what it costs to enjoy a chalice of wine each week!

So, now when I look up at the stars, I see not just the vast numbers, but count the brightest ones–the ones “For Whom the Grail serves!” And we, the sponsors, are the Fisher Kings!